Illogical Dates, Missing Parents, Bastardy Bonds: What to Do If Your Ancestors Were Born Out of Wedlock

Last Updated September 29, 2020

Ancestry 50% Off Gift Memberships for Black Friday (Gift to Anyone, Even Yourself!)

By Patricia Hartley

When you are new to family history research, it’s easy to imagine that every ancestor will fit neatly into a perfect family group: father, mother and children. They’ll live together in one household in the census, share the same last name, and first births will occur at least nine months after a marriage.

It doesn’t take long to discover, though, that our ancestors’ lives were as complicated as ours are today. They divorced, lived together without marrying, cheated on their spouses, and had children before marriage (or even while they were married to someone else).

Sometimes you stumble upon these mysterious children or illogical dates by accident, and then work to figure out how this person came about. Other times, you suspect a child was born outside your expected typical family group and focus your research on proving their legitimacy or “illegitimacy.”

Make Instant Discoveries in Your Family Tree Now Imagine adding your family tree to a simple website and getting hundreds of new family history discoveries instantly.

MyHeritage is offering 2 free weeks of access to their extensive collection of 20 billion historical records, as well as their matching technology that instantly connects you with new information about your ancestors. Sign up using the link below to find out what you can uncover about your family. Discover New Genealogy Records Instantly

These confusions can mean that fathers, and sometimes mothers, may not be who we thought they were. And, despite the fact that families come in many shapes and sizes, for family historians it is so important to fully understand family relationships so that we can correctly place someone in our family tree.

Also read: Who Counts as Family in a Family Tree

Clues to to Help You Discover if Your Ancestor Was Born Out of Wedlock, and What to Do Next

So how do you know when an ancestor was born out of wedlock? As you’ll see, some clues are more straightforward than others.

Illegitimate Terminology

There are certain terms that have been used throughout the centuries to refer to children born out of wedlock, and finding one of these is an easy way to determine someone’s birth status. Some of those terms are no longer used, and many are considered offensive today. However, as with any other aspect of social history, we have to understand that they were a product of the time and understand the context in which they were coined.

Some keywords to watch for in historical records include:

IllegitimateBastardBase-bornReputed (the father accepts the child as his, or the child has been proven to be his)Imputed (the father denies the child is his)MisbegottenNaturalIgnotis (Latin for “unknown”)

Other countries used different terms, sometimes assigning the child a surname that in their language meant “unknown,” “cast out,” or “foundling.”

20 Billion Genealogy Records Are Free for 2 Weeks Get two full weeks of free access to more than 20 billion genealogy records right now. You’ll also gain access to the MyHeritage discoveries tool that locates information about your ancestors automatically when you upload or create a tree. What will you discover about your family’s past?

Claim My Free Record Access Now

Family Lore

You may have heard whispers of illegitimacy at reunions or when older family members are asked about a certain ancestor. In many families, the illegitimacy of a child was common knowledge among cousins, even if the child was never told. Sometimes this information was passed down among generations whenever that family member was mentioned. Look for clues in your family lore or in old personal documents.

“Unknown Father” on Vital or Church Records

This one can be tricky, because a father’s (and mother’s, for that matter) name is often left off of a death certificate simply because the informant doesn’t know or remember the information.

Birth certificates, however, are a different story. Official, or certified, birth records were required in every jurisdiction across the United States by the early 20th century, and many large cities kept birth registers for years before that. In most cases, the mother or a close family member provides the information that is listed on a birth certificate or birth record. The same is true for church baptism or christening records.

Because these events occurred so soon after a child’s birth, an “unknown” father in the record often points to a child born out of wedlock.

Illogical Ages or Names

Sure, our ancestors had very large families, which meant that fathers and mothers were having children well into their older years. But when you see a census record with a mother who is 48, with children aged 29 to 12, followed by a child of the same surname but age 2, it could indicate a child who belongs to the father, but not the mother.

Of course, there are other explanations for this, such as the child being a grandchild or someone who was adopted and given the family surname, but it’s worth exploring further. In the same vein, if you see a record listing a child with the maiden name of the mother, it could be a case of illegitimacy.

Another “out of wedlock” scenario is when a child’s birthdate occurs less than nine months after a couple’s marriage. I’m still trying to figure out the mystery of my own grandmother’s first child. My grandparents were married on April 5, and their first child was born on May 17 of the same year. If this was a shotgun wedding, they waited until the last minute! So is it possible the child belonged to another father and my grandfather valiantly stepped in to marry a girl who was “in trouble?”

The child died when he was only two years old, so few records exist, and DNA isn’t an option. The couple went on to have seven more children, five of whom lived to adulthood. But the story about that first little boy is still a conundrum.

Probate, Wills, and Orphans Court Records

Some men would mention their illegitimate child(ren) in their will to indicate their wishes to include or exclude the children from the division of assets. Probate records may also mention these children even if they aren’t in the will if those children’s existence was made known after the father’s death.

Bastardy Bonds

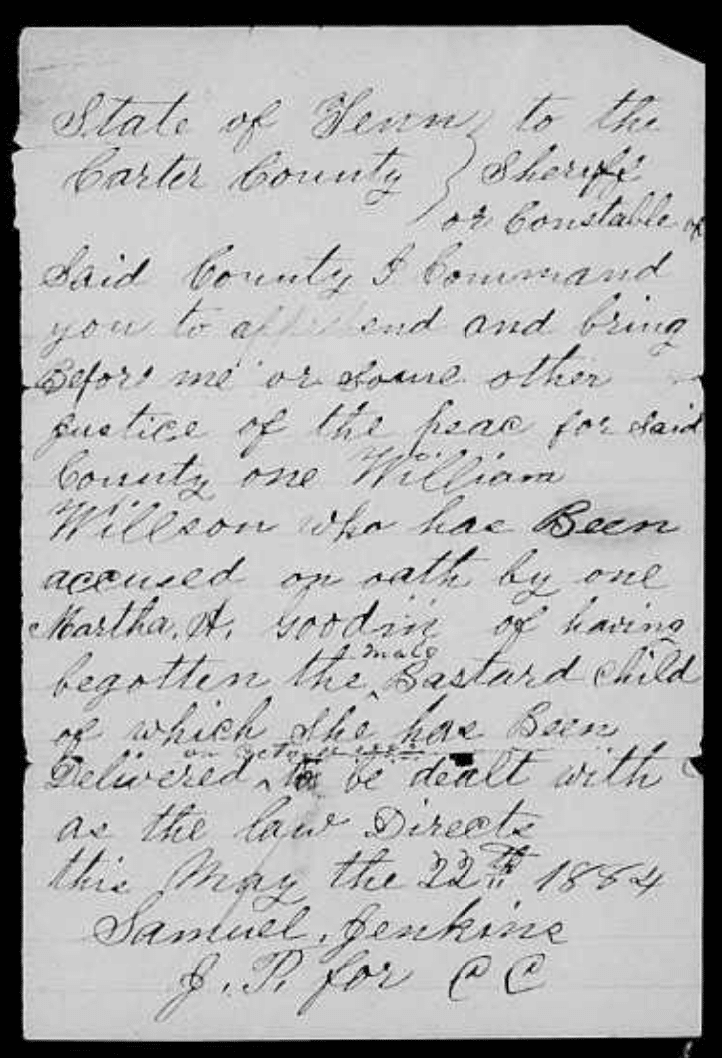

The most obvious and helpful court records pertaining to illegitimacy are bastardy bonds, which may turn up in your research. These documents named the father of an illegitimate child as well as the mother who claimed his paternity.

They usually demanded that the father take responsibility for the financial support of the child, because if the mother couldn’t adequately support the child, he or she would most likely become a burden to the government. A bastardy bond is more than a clue; it’s actually a solid lead to the identity of an unknown father and confirmation that a child was born out of wedlock.

Conflicting DNA

One of the inadvertent effects of widespread genealogical DNA testing has been the discovery of previously-unknown family members. It’s nearly inevitable to connect with someone in your DNA match network only to find they are the illegitimate offspring or a descendant of an out of wedlock union of a distant cousin, great-great-uncle, or even a grandparent.

I’ve personally encountered this scenario four separate times with my own family’s DNA matches! In most of these cases, the person reached out to me to ask for help figuring out how we were related, as they knew they or their ancestor were illegitimate.

What to Do if You Do Find an Out of Wedlock Birth and Can’t Find the Father (or Mother)

When you come across any of these clues to illegitimacy in your genealogy research, they definitely pique your interest. On their own, though, they don’t tell you much, and it’s sometimes difficult to prove an out of wedlock situation on the merits of one blank space on a document.

It’s important that you continue to gather as many documents or family accounts to first, prove — or disprove — illegitimacy, and second, find the true identities of the child’s parents. Here are a few places to start:

Ask Your Family Members

You probably started your genealogy journey by interviewing the oldest members of your family, but at the time, you may not have known to ask about children born out of wedlock. This can be a touchy subject, so approach it with caution.

You may ask, for instance, “Have you heard any stories about Great Uncle Joe’s father?” rather than blurting out, “Was Great Uncle Joe illegitimate?” If one family member is reluctant to talk about this ancestor, try asking another person who might be interested in sharing with you.

Check the Papers

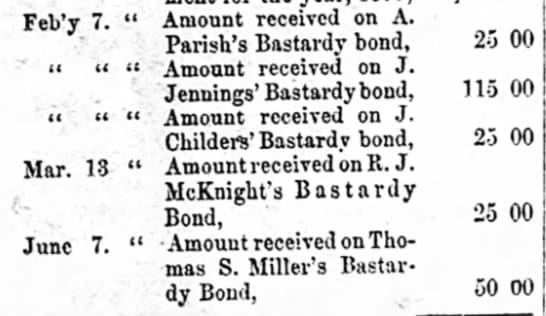

Since the goal of bastardy bonds was to collect money from the father for support of the child, these payments were often recorded in the local newspaper. The account below was printed in the York, South Carolina Yorkville Enquirer in 1856:

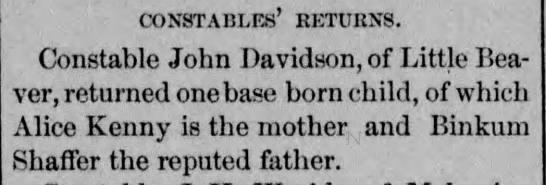

If you’re not sure where to start, find the local newspapers where your ancestor was born and limit your search to the first five or so years of the child’s life. Use search terms such as “bastardy,” “base born,” or “reputed” and the child’s last name to narrow your results. Your search may also yield notices of court proceedings involving paternity, like these from 1870 Massachusetts and 1889 Pennsylvania, respectively:

Look for Actual Bastardy Bonds

Not every state kept records of bastardy bonds and even fewer of these have been published in online databases. However, if you suspect your ancestor may be illegitimate, it may be worth a call to his or her birth county to see if bastardy bond records are available, and if so, plan an onsite visit or request they mail you a copy (if they offer look ups for a small fee). These types of records may also be filed under “miscellaneous,” “loose records,” “orphans,” or even “guardianship” records.

Compare Original and Amended or Delayed Birth Certificates

Often, a mother would leave a father’s name blank on a birth certificate and later amend the certificate to include a name — or vice versa, as they may name the father on the original and remove his name in an amended version.

If an amended birth certificate was issued, it should accompany the original when ordered from your particular state or county. A delayed birth certificate, which became more common after 1937 when obtaining a Social Security number required proof of birth, can hold quite a bit of information as several unique records or testimonies were required to prove what the person had provided.

Look for Suspected Fathers

Sometimes — well, often times — genealogy requires trial and error research. You might have to spend some time traveling one path, only to find out it’s a dead end and you have to return to your starting point. Trying to identify an unknown father or mother can require this type of journey.

Depending on the era, you might check the census records of your ancestor’s mother, looking for neighbors who might have been the right age or older when the mother became pregnant. Maybe you notice one man’s name appearing repeatedly in other documents where your ancestor is mentioned. Perhaps the mother was employed by a wealthy (possibly married) man or worked with someone closely.

These tips are also good when looking for missing mothers as it was not unheard of for a wife to “adopt” or raise her husband’s illegitimate child, or employ that child in a home or business – meaning the biological mother may not be listed in records with the child.

Once you identify a “suspect,” spend some time studying that person’s life and records, especially wills and probate documents, land transfers, and even family stories other researchers might post online. If possible, use DNA results to eliminate non-contenders, as well.

Double- or Triple-check Records in Your Collection

No matter how long you’ve had the 1860 U.S. Federal census record in your collection for the ancestor in question, it’s worth reviewing it and his or her other records again for clues.

Perhaps someone slipped up and listed the child with the father’s surname instead of the stepfather’s or mother’s, and you always assumed it was just an enumeration error. Maybe there’s a note written in the margin of an old newspaper clipping that you’ve overlooked. Once you have the context of the person’s potential illegitimacy, you’ll view all of these records with new eyes.

Also read: Why You Should Stop Your Research and Reexamine Every Single Genealogy Record You Have & 5 Uncommon Places to Find Your Ancestors’ Missing Parents

For nearly 30 years Patricia Hartley has researched and written about ancestry. She has a B.S. in Professional Writing and English and an M.A. in English from the University of North Alabama and a M.A. in Public Relations/Mass Communications from Kent State University.

Leave a Reply